Some parents offer little in the way of care for their offspring. Many insects will glue their eggs to the underside of a leaf and leave the hatchlings to fend for themselves. Green turtles will bury their eggs in sand and then abandon them, leaving the eggs otherwise unprotected and the future hatchlings on their own. Caring for a clutch of eggs, however, will greatly increase chances of survival. Birds care for their eggs in nests or leave them with an unwitting host in the case of the cuckoo. A certain species of frog even goes so far as to store eggs beneath the skin of the males - what is more, the eggs are not ejected before they hatch.

Brooding behaviours are seen throughout the fossil record. Yet remarkable fossils from the Burgess shale assemblage demonstrate the existence of a particular type of brooding strategy 505 million years old. The fossils in question belonged to a species of arthropod known as

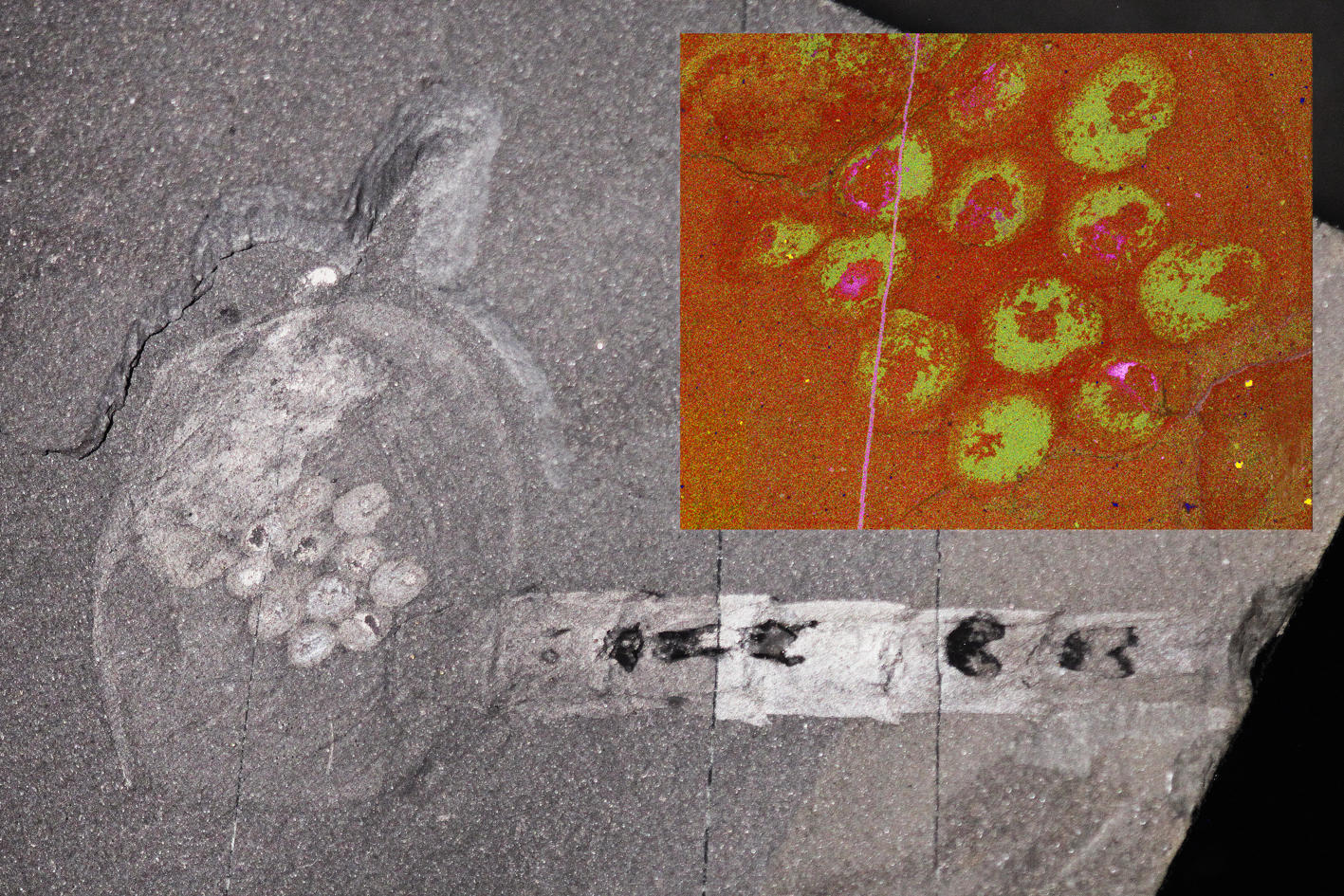

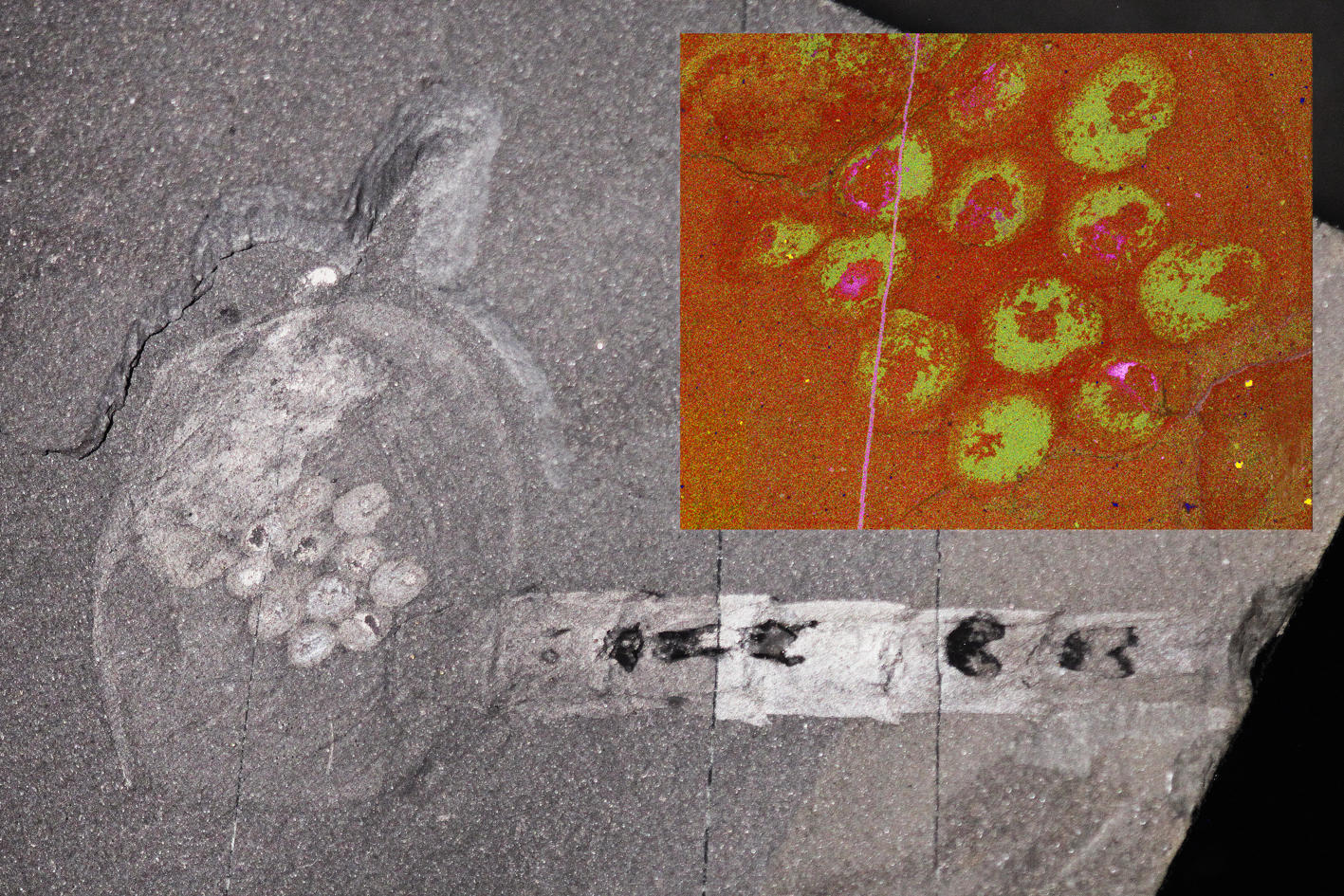

Waptia fieldensis which shares similar features with many arthropods, and as such, is classified as a close relative, albeit tentatively. The specimens used in the study had a series of white blobs arranged around the carapace. Using a combination of photography, electron microscopy and elemental mapping, Jean Bernard Caron from the Royal Ontario Museum and Jean Vannier at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, France, were able to demonstrate that these represented a clutch of eggs.

|

| Waptia specimens with the egg clusters highlighted |

The carapace of the parent provided a substrate onto which the eggs could be anchored, but with the added advantage of parental protection and an environment kept well oxygenated by ventilation - ideal for developing embryos.

'This creature is expanding our perspective on the diversification of brood care in early arthropods,' said Vannier, the co-author of the study. 'The relatively large size of the eggs and the small number of them, contrasts with the high number of small eggs found previously in another bivalved arthropod known as

Kunmingella douvillei. And though that creature predates

Waptia by about seven million years, none of its eggs contained embryos.'

The smaller clutch size in

Waptia would have allowed the parent to devote more parental care to each egg and possibly the offspring compared to what

Kunmingella could offer. In turn this would increase the chances of survival of each egg and hatchling. The Cambrian was a time of great change ecologically, anatomically and phyletically. Increasing complexity would undoubtedly have brought about new and complex behaviours. Yet brooding behaviours are only a recent discovery. The insight they may provide into the mechanics of the Cambrian Explosion is yet to be fully explored.