|

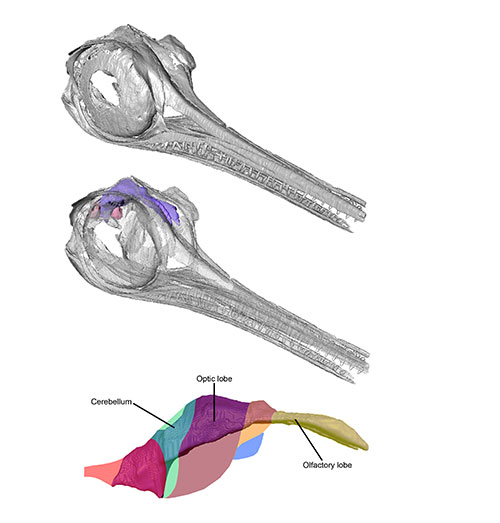

| The digital reconstruction of the skull and brain of Hauffiopteryx typicus |

By infilling the digital cavity within the skull, the researchers were able to create a model of the brain. They found enlarged optic lobes, which correspond to the specimen’s huge eyes and allowed it to see when diving to deeper, darker waters after deep dwelling species such as ammonites or squid. The ichthyosaur also had an enlarged cerebellum, the part of the brain responsible for motor control, enabling it to be a highly mobile, visual predator. Additionally, the olfactory region, the area responsible for processing smell, was enlarged, adding to an already formidable sensory array.

'These results both confirm previous hypotheses on ichthyosaur sensory biology and also offer new insights into how these marine reptiles interacted with their environments,' said Dr Michael Benton from the University of Bristol. 'Perhaps the creatures relied more on their sense of smell than we previously thought.' As land dwelling mammals we sometimes forget that while our sense of smell cannot operate underwater, aquatic creatures have developed alternate sensory systems which perform the same function. A sense of smell in ichthyosaurs adds a whole new dimension to the Jurassic seas.