|

| The 165 million year old fossil of Megaconus mammaliaformis |

A closer inspection of the haramiyid revealed a sparse covering of hairs on its abdomen. What is more, it possessed a keratinous spur on its heels similar to that found in the male platypus, suggesting that this creature was also male. Whether it was poisonous like that of the platypus we cannot say, but it shows that the creature, now named Megaconus mammaliaformis, possesses strange biological affinities.

'Megaconus confirms that many modern mammalian biological functions related to skin and integument had already evolved before the rise of modern mammals,' said Zhe-Xi Luo from from the University of Chicago. Even so, its classification was problematic. The 160 million year old haramiyid Arboroharamiya, which was also discovered by Zhe-Xi Luo, had fur and a jaw composed of a single bone, a feature only seen in mammals.

|

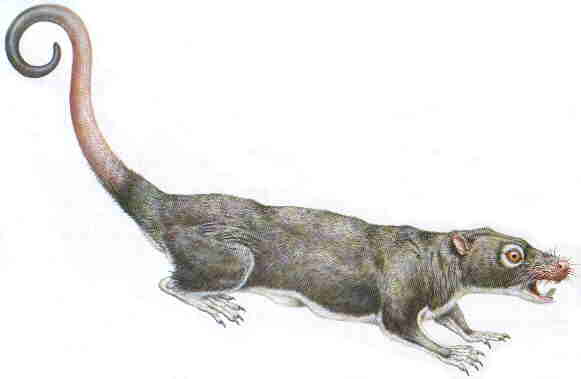

| An artist's impression of the 165 year old mammaliaform Megaconus mammaliaformis |

Its construction would also suggest that it had mammalian ear bones as well. To investigate its evolutionary relationships, researchers analysed over 400 anatomical features from over 50 different species of ancient mammals with a temporal range of between 250 and 100 million years ago. Their calculations placed Arboroharamiya firmly within the mammal group. Their data also indicated that the first mammals, in the form of haramiyids, first evolved between 228 and 201 million years ago.

Similar analysis for Megaconus returned surprising results. Despite being in the same group at Arboroharamiya, this new species with its reptile-like ear, ankles and vertebral column simply did not fit with the existing scheme of classification for the haramiyids. The new data shows haramiyids, including Megaconus, branched away from the other mammalian lineages 40 million years prior to the evolution of true mammals 160 million years ago. This satisfies the haramiyid origin at around 200 million years ago and suggests that the common ancestor of all living mammal groups lived 180 million years ago.

|

| Is it possible that Arboroharamiya was actually a multituberculate? |

What is more, it would suggest that the common ancestor of the haramiyids and the rest of the mammal groups also possessed hair. Such a creature would have lived long before the first true mammals, showing that one of the defining traits Carolus Linnaeus identified is not as clear cut as we once thought, having first evolved in a reptile rather than a mammal.

So where does this leave Arboroharamiya within the mammal group? According to Guillermo Rougier from the University of Louisville, Kentucky, it is possible that this creature may actually be part of the long lived and highly successful, but now extinct mammal group, known as the multituberculates.

So where does this leave Arboroharamiya within the mammal group? According to Guillermo Rougier from the University of Louisville, Kentucky, it is possible that this creature may actually be part of the long lived and highly successful, but now extinct mammal group, known as the multituberculates.

This, at least would explain the disparity between the family trees drawn up independently for Megaconus and Arboroharamiya. The origins of mammal groups during the Mesozoic era is a highly contentious subject. Fossils are few and far between and what fossils do exist consist primarily of teeth. This makes it challenging to find the links between species and define the evolutionary pathway which led to the first true mammals. With each new study, however, we define a part of this story: whether through tireless phylogenetic analysis or palaeontology's answer to the Rosetta stone. We will understand where our warm blooded, fur-covered family came from.