|

| The 315 million year old, world record breaking trackway from Joggins. The long thin marks in between the footprints were created by the tail dragging on the ground |

In my last post, I described the tracks of a horseshoe crab which were used to retrace its life and moment of death. The size and shape of footprints link to the creature; the depth, the way it moved.

Age is also important: ancient trackways have pushed back the dates of some of the most important events in palaeontology, such as the invasion of land and the appearance of many different animal groups. Many footprints are massive. Indeed, there are rock formations covered in the tracks of entire herds of giant, extinct reptiles. Yet the scale works both ways. Recently the smallest fossil footprints ever have been unearthed.

The 315 million year old, Carboniferous cliffs at Joggins in Nova Scotia, Canada, are sometimes referred to as the Coal Age Galapagos on account of the incredible diversity of unique species found in the rocks on its storm-lashed coast. Earlier this year, an amateur palaeontologist hunting at the Joggins cliffs recovered the tiny tracks of a species of vertebrate. 'When I saw the very small tail and toes I knew we had something special,' said Gloria Melanson who uncovered the tracks. 'I never thought it would be the world’s smallest.'

|

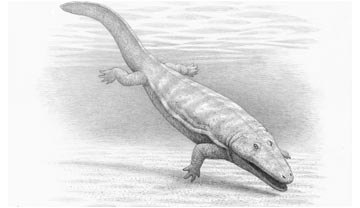

| An artist's impression a temnospondyl amphibian |

It is likely that the tracks were made by a temnospondyl amphibian or microsaur. As I said earlier, many trails often tell a story. While this particular specimen is quite small, it clearly showed that the creature began walking, changed direction and then began to run. The researchers have hypothesised that it may have been chasing an insect or, if it was an amphibian, taken its first tentative footsteps onto dry land after transforming from a tadpole.

While this last hypothesis is unlikely, I would like to believe that it is true. It would be truly incredible if we had, in our collections, the traces of an ancient metamorphosis, a single moment in time, preserved for eternity. The rocks at Joggins contain everything from the remains of an ancient forest to the first ever reptiles on the planet. They will continue to throw up surprises of the utmost scientific importance.