|

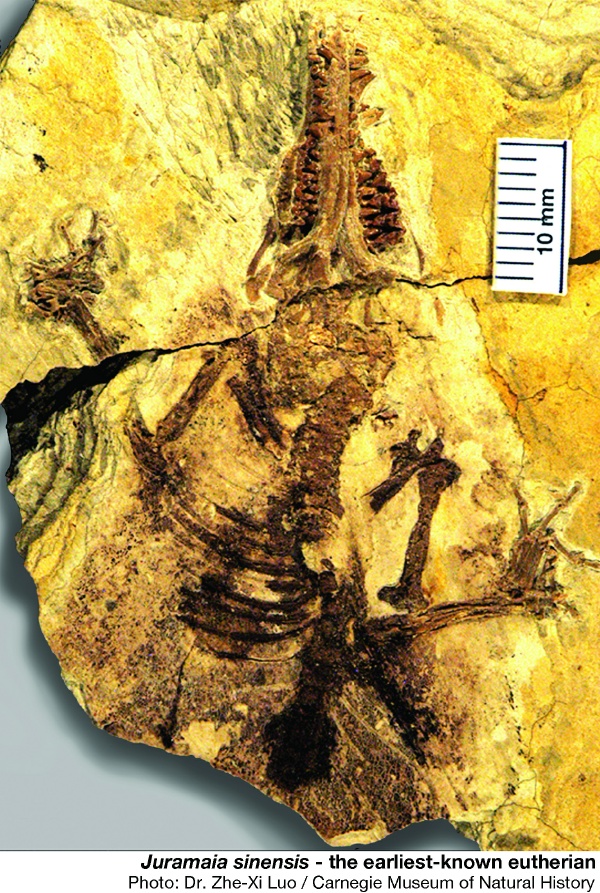

| Juramaia sinensis, the oldest known placental mammal |

The real question is not only why, but how mammals moved away from egg laying or pouches and evolved the ability to give birth to live young which are essentially miniature versions of the species adult form. The why is easier to answer. If the young can develop to such a stage that they can suckle and possess some basic modicum of movement, then they are far more likely to survive into adulthood than if they were laid as eggs.

The how is a more thorny conundrum: how did mammals evolve a completely new, very complex and highly specialised body organ? Mammals had evolved tens of millions of year before and were perfectly adapted to egg laying. However a research team led by Dr Gunter Wagner, the Alison Richard Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Yale University, have conducted a genomic study which they believe sheds light on this palaeobiological mystery.

|

| A diagram giving a simple explanation for how transposons affect their host's DNA |

Transposons are often grouped in with junk DNA and therefore were once considered unimportant parts of the genome, with no real effects upon the organism. We now realise that a lot of junk DNA simply directs the interpretation of the rest of the genome. 'In the last two decades there have been dramatic changes in our understanding of how evolution works,' said Dr Gunter Wagner 'we used to believe that changes only took place through small mutations in our DNA that accumulated over time. But in this case we found a huge cut-and-paste operation that altered wide areas of the genome to create large-scale morphological change.'

Mammalian transposons specifically affect mother-fetus communication and various cycles and functions during pregnancy by expressing or repressing certain gene sets. The Yale team studying the evolutionary history of pregnancy looked at cells found in the uterus associated with placental development. They compared the genetic make-up of these cells in opossums -- marsupials that give birth two weeks after conception -- to armadillos and humans, distantly related mammals with highly developed placentas that nurture developing fetuses for nine months.